The Diamond Ring of Decision-making

Complex problems require a different approach.

In my I wrote about Sam Kaner’s Diamond of Participatory Decision-Making, which has always helped me think about what authentic collaboration feels like. It can be hard work.

The diamond shows us that after some ‘groaning’ we get to a point where we can converge on an outcome or outcomes, which has always been very encouraging. Yet I also know that when confronting our more complex and intractable problems the reality is that we rarely get to ‘the answer’.

For example, improving water quality and management at a catchment level is one of those ‘forever’ problems that never really go away. Catchments and all that goes on within them are an ever-evolving suite of dilemmas, dynamics, pressures and responses. We can always improve what we do, but the problems are never ‘solved’.

So what does this mean for the diamond of participatory decision-making? As a map for visualising how we tackle complex problems, perhaps the diamond is actually a circle. Rather than getting to the end, we continuously cycle back, through periods when our thinking is diverging and periods when our thinking is converging.

I have tried to illustrate this idea here.

I see this journey as a cycle of learning. In a way we never leave Kaner’s ‘groan zone’. Rather we recognise that when dealing with hard problems we are always sitting with uncertainty, incomplete knowledge, unintended consequences, different worldviews and different ideas. While outcomes are always important, our overarching approach is not about finding ‘the answer’ but about constantly finding new questions to ask and new ways to test our understanding and our ideas. Dave Snowden of fame suggests we “probe, sense and respond” in the complex domain. That is, we test ideas. When we find things that seem to work, we do more, building on success while always watching for signs that this is no longer delivering.

One way to look at this cycle is to see that it is groaning all the way down! But let’s embrace the complexity and reframe our approach from groaning to growing, from solving to learning, from convergence on the answer, to convergence on ideas as we go.

Perhaps this is the diamond ring of participatory problem solving?

Resetting your collaboration

In Stuart’s , he identified some signs that a reset might be necessary. Let’s look now at what a reset might look like….

Having decided that something needs to be done, the typical response is to focus on structural, process and content issues. For example, the way we are set up, and the way people are working, especially the behaviours we see and don’t like, redesigning meetings or agendas, getting a better facilitator, managing the meeting dynamics better, calling out poor behaviour, etc.

While these might help, a much more useful approach is to focus first on the relationships. You might think of this like the Titanic and the iceberg - it’s what’s below the waterline that can sink the collaboration. And the relationship element is below the waterline; harder to see and trickier to deal with, but much more likely to allow smooth sailing when tackled.

Healthy collaborative relationships create a safer and more stable working platform in which to deal with current and emerging issues. So what can help reset the relationship and set you up for success in your collaboration?

- Acknowledging the history. Often there is baggage around what has happened before that impacts our behaviour, for example a past event that sticks in our mind and causes us to mistrust what others do. Surfacing some of that history and the consequences for each of us can help clean up the baggage. While this might be seen as opening old wounds, unacknowledged baggage can paralyse interactions, while respectful inquiry and acknowledgment in a safe environment can allow people to move on

- Checking and testing assumptions. Making visible our respective assumptions can be quite revealing, and allow us to test and explore the views we hold about others, and they about us. We can be quite surprised, and sometimes shocked (how could they believe that about us…..?), but we are then in a position test them and consider the implications for our work together. This can be quite cathartic, providing new insights and understanding of why people (us and them) may act the way we do.

- Putting yourself in the other’s shoes. This is where you try to see the world from the other person or group’s perspective. What really matters to them? What do they deeply care about? What makes them tick? What does their boss look for in their work? For example, one group might value social equity, and another may value technical expertise. If each perceives any situation only from their own perspective, misunderstandings and assumptions about motives might make it really challenging to find solutions together, leading to confusion and frustration. Taking time to hear how others think and work provides more shared understanding, facilitating more useful joint action on the difficult issues.

Sometimes clients are concerned that these activities will take time and distract from getting solutions. On the contrary, such reset activities can be a critical and essential investment in a robust working relationship, avoiding risks to solving key issues of structure, process and content. Is it time to reset your collaborative relationships?

What migraines taught me about overmanaging

I suffer occasional migraines which can be quite debilitating, especially at work when you just can’t concentrate and you just want to lie down and close your eyes.

I now manage them overnight with some specific medication, but previously they would impact me when I was facilitating group work.

On one occasion I was working with a group and was keen to help them get a good outcome. I would usually ensure the process was well designed and organised, pay close attention to the relational dynamics, and intervene throughout to help them.

In this case, I woke with a migraine, and dragged myself to the meeting feeling pretty terrible. Given my state I did the minimum setup and just relied on the group starting the conversation about the topic. Feeling as I did I had no energy to intervene, so just had to sit there and let it happen around me.

To my surprise, I found the group functioned remarkedly well, and maybe achieved more in terms of both their relationships and the difficult topic than I could have hoped.

When I felt better, I reflected on my insight, and subsequently tested my hypothesis around intervening less.

My learning that day has helped inform my practice- that stepping back, intervening less, and trusting the group is powerful in getting better outcomes.

That doing less is actually more.

Overcoming the inertia- just try stuff

We often encounter clients who acknowledge the roadblocks to progress, but seem paralysed in their attempts to deliver substantive change.

I hear a lot of words like ‘until’ and ‘when’ and ‘if’ :

- when the restructure is complete, we can change how we work

- if only I could get commitment from the leaders, then we could try that

- we just need to get the plan sorted, then we can tackle that issue

- when we have built the strategy, we will be able to work differently

- if only people would step up and take responsibility, then I wouldn’t have to keep fixing things up

And the reality is that we never get there- we are always waiting!

It reminds me of Judy Garland and that song - ”Somewhere, over the rainbow…..” , in the hope that our dreams can come true.

Of course the last line is quite prophetic in this context- “Why, oh why can't I?”

Interestingly I also see a frustration from leaders in response to such comments…

- I’m committed, how many times do I have to tell you…?

- you don’t need to wait, we can do it now…

- they can take the lead without us….

I’m intrigued by this dynamic, and hypothesise that experimentation could be a way to break this seeming impasse.

So what might such experimentation or piloting look like?

Rather than needing to know, to wait, to be sure, then perhaps a way forward is an ‘and’ ie to do something while still waiting and planning, etc

This would mean actioning a series of small parallel actions to address the topical issue, while still working on the roadblocks:

- working in a new structural arrangement while organising the restructure

- assuming commitment is there and taking some different actions based on that assumed commitment

- trying something while developing the plan

- trying two ways to tackle the same issue rather than relying on the favoured option

- testing elements of the strategy before it is released

- saying yes to something where the natural and safe option is to say no or avoid taking it on

It would seem to make sense to select small initiatives that you feel OK to try, and that wouldn’t compromise critical aspects if they didn’t work, but may inform you with alternative pathways to success.

Perhaps just ‘trying stuff’ (and living with a degree of uncertainty) can overcome that frustrating feeling that we can’t progress.

Experimenting with Siri

In which some experimentation with Siri got me where I needed to go.

Yesterday afternoon was a typical one for me in many ways. At 2:30 or so I jumped in the car for the three-and-a-half-hour drive to Lake Macquarie City Council to run an intro to collaboration workshop for new and returning Councillors. I have done that drive so many times that I have long suspected that my car could drive itself.

If only.

Turns out there had been an accident on the M1 Motorway and traffic was backed up to a hopeless degree. Soon Siri was telling me I was going to miss my workshop start time by 60 minutes. I needed an alternative!

I had no idea if any alternatives would be better. I didn’t yet know what the problem was, where or how bad. I was trapped in the limitless traffic snarl that was Northwestern Sydney. Yet I couldn’t afford to sit where I was, so I recruited the ever faithful Siri into a process of experimenting the way forward together. That means, I developed some quick hypotheses about alternative routes and tested them. Importantly, I needed to try only those ideas that were safe to fail, that is, that were likely to be no worse than the current scenario. And as the current scenario had me arriving way too late to deliver my workshop, I had some scope to try other ideas, even if they didn’t feel quite right.

So, I picked an alternative destination along my route and Siri plotted the course. She directed me to some odd places but at least we were moving. And then I turned on the radio to check the traffic reports and I quickly gathered some data that Siri didn’t have, about the specific accident and likelihood of clearing up. This gave me some other ideas, and with Siri’s help we tested some new alternatives. One seemed likely to be better so we tried it.

Stop…start…stop…start…stop…. This wasn’t looking good and my goal seemed unachievable. Then more data came via the radio. It seemed that the accident had been cleared up. Siri was directing me to turn left but based on the new data I developed a new hypothesis and went right instead. Good old Siri stuck with me even though I ignored her ideas and, as fortune would have it, the traffic began to move and we were on our way.

The workshop was scheduled to begin at 7:10 and I pulled into Council’s carpark at 7:09. Job done, though I was feeling a little frayed around the edges after close to five hours of traffic jam. But when we collaborate through complex, uncertain and challenging problems it’s not unusual to feel a little exhausted.

Siri and I got where we wanted to go through a process of testing and learning the way forward together. At no time could I be sure that my choices were going to work, but I didn’t let that paralyse me. Instead I embraced the uncertainty and experimented creatively. By good luck and good management we found a solution in a very dynamic and unknowable situation.

I learned two things on my journey to Lake Mac last night. Firstly, this experimentation thing really works. And secondly, Siri could teach us all a thing or two about collaboration.

The Three Steps of Authentic Collaboration

Our projects may be complex, uncertainty may be high and the thought of collaborating may be quite daunting, yet we can take comfort in three simple steps for working with others on our most challenging problems. These steps don’t make collaboration easy but they do provide us clear guidance on our journey together.

Step 1: Share the problem

You are collaborating on something, so what is that thing? What is the problem to be tackled, the dilemma to be resolved, the project that needs delivering? This step is about getting everyone in the room (actually or metaphorically) to share how each sees the problem from their own perspective. Resist the urge to leap to solutions and resist the feeling that you know what the problem is. Encourage sharing, listening, learning and building a collective sense of the situation in all its juicy complexity. Sit with the dilemmas, without trying to fix them.

Step 2: Share the direction

You’ve built a picture of the problem. Step two is to look ahead and co-create a shared idea of what ‘solved, resolved or delivered’ would look like. Paint a picture together of what success looks like. Importantly, the aim here is not to solve the problem. Rather the aim is to agree a distant ‘light on the hill’ or destination to which you can all aspire. Keep your brush strokes broad and detail to a minimum while setting a clear direction. Not ‘we need to close the street and ban cars’ but rather ‘we seek a town centre that is attractive, where people want to spend time and relax’. That’s your shared direction, your light on the hill. You may never get there, or achieve a perfect outcome, but you know where you are heading together. Now on to step three.

Step 3: Share the actions

You’ve agreed a shared sense of the complex problem you face together. You’ve agreed a direction you want to head. Now it’s time to begin to move towards that light on the hill. Because your problem is complex and uncertainty high, it’s important to reframe your normal problem solving approach. There may well be no ‘solution’ to your problem so your task now is to work together to identify steps you can take that are likely to move the situation in the direction you’d like to head. What small actions can you think of to try? What small changes or tweaks can you readily make? What ideas can you test together? How many can you do in parallel to ensure you are moving quickly? Resist the urge to land on ‘the answer’. Rather, focus on learning the way forward together, seeking constantly to move towards your agreed light on the hill.

A key part of what you are doing through these steps is ensuring that all stakeholders have their fingerprints on the problem to be solved, the aspiration that generates energy for working together, and the actions, learning and problem solving required.

So, though our problems might be complex, the three-step framework for collaborating on those problems is relatively straightforward. Good luck!.

Just Try Stuff....

I was prompted by Stuart’s blog to dig a little deeper into one of the learnings from the pandemic.

“Just try stuff” was about recognising that a key characteristic of a complex situation like a pandemic is uncertainty about what to do, and about the only thing you can do is to try something and see what works.

We have seen that happening constantly through the last 18 months, both in responding to the health crisis, and also dealing with the social and economic consequences.

What has been interesting to me has been the shift from an initial belief that we knew what to do and could predict and plan actions, to a growing realisation in the value of trying a range of approaches, while keeping a close eye on the results, and then modifying quickly based on the results.

Now while it did seem a bit like they were “experimenting” on us, there is little doubt that keeping everyone as safe as they could while learning what worked has been a feature of the response worldwide.

And while our leaders have copped some criticism for their approaches- slow to respond, inconsistent, etc, perhaps they were being judged by conventional thinking that just doesn’t work when challenged by this level of unprecedented complexity.

The features I think we learned around action planning that we can take into our ongoing co-design activities include:

- feeling a bit uncertain is a characteristic of tackling complex situations

- it’s OK to be unsure what to try next

- letting go of the “right answer” is hard but appropriate

- multiple small and short “experiments” make much more sense when tackling complexity

- keeping the activities “safe to learn” is key to gaining support

- reviewing progress regularly against the goals provides confidence

- and not being afraid of ending something and trying something else based on the results

So while we still haven’t yet “solved” the pandemic, it has allowed our political, business, health and community leaders to see that “trying stuff” rather than always knowing what to do is a useful alternative approach in our complex and ever changing world.

Even when they don't want to collaborate, you have choices...

A question that we keep hearing clients is "how to collaborate with the unwilling?".

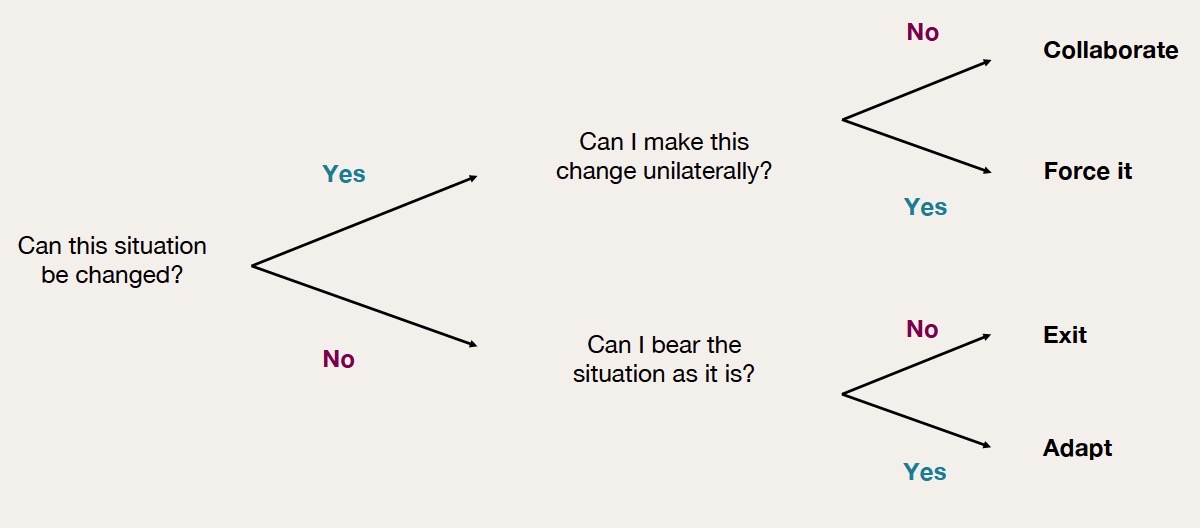

It is often framed as if being 'unwilling" is somehow not acceptable, and that there is no alternative. It reminded me of the Kahane Framework that I blogged about last February:

A couple of years ago we came across a really nice decision-making framework that has been particularly useful in helping clients with the choices around collaborating or not.

It was developed by Adam Kahane, and outlined in his book “Collaborating with the Enemy” (Berret-Koehler, 2018)

In the framework, Adam suggests that when faced with a difficult situation, one can respond in 4 ways- collaborating, forcing, adapting or exiting-

He suggests that one should choose to collaborate only when it is the best way to achieve the objectives. So this means collaboration is appropriate when adapting or exiting are hard to swallow, and forcing is impossible because one can only succeed by solving with others (multilaterally).

Adam also notes that the choices can be situation and time dependent, and one may move between the choices (for example between collaborate and force) over time or as circumstances change.

So such a framework can remind us that we may have a lot more choice than we think when faced with intransigence and opposition, and that we can still be in the drivers seat by choosing a different pathway.

So if you feel stuck when facing opposition to your collaborative intent, cut yourself some slack, stop blaming and open up to some different options.

Just Try Some Experimentation

I have a client I have been coaching for some time. Let’s call him Rob. He’s a senior guy in a business with a nationwide footprint including multiple offices of widely varying sizes. One of Rob’s key responsibilities is to take the Strategic planning process forward, building the cascade from corporate strategy to section objectives to team actions and personal KPIs. Importantly, Rob wants to do this work collaboratively as part of an organisational aspiration to be more collaborative in its culture. And he also has to fit everything into the frameworks provided by their multinational owner.

So it isn’t a simple task, and in our regular conversations I see Rob grappling with the question “how am I going to do this?”

Understandably, Rob finds the task very uncertain and challenging, even overwhelming at times. What he dearly wants is the answer and until he finds the answer I see him sometimes spinning his wheels and losing confidence.

I can’t give Rob the answer or tell him how to do this. Nobody can. This task is a complex one, both very alike the situation in similar organisations, yet unique in its own ways. What I have been able to help Rob gain is the confidence to admit he doesn’t know, to understand there isn’t a right way, and to just try things. Rob has shifted from problem solving mode to learning and testing mode. And the difference has been amazing. In recognising the inherent uncertainty, complexity and ‘unknowability’ of the situation Rob has been able to cut himself and his people some slack.

- He lets go of the need to have ‘the answer’.

- He trys different things and learns how to build the frameworks as he goes.

- He takes small steps with confidence, learning as much from the things that don’t work as from the things that do.

For example, Rob wants teams to report back against their agreed objectives and KPIs. He was struggling to come up with the ‘right’ questions that would gather the ‘right’ data. Then with his experimenters hat on he decided to test different sets of question in different offices, to see what was going to work best.

Now at the check-out from our coaching calls I hear Rob use phrases such as “I’m really looking forward to trying this” and even, “I’m excited about the next step”.

There is real power and freedom in that mindset shift from “why don’t I know how to do this?” to “what can I try next?”.

So why not try a little experimentation?

If you want to learn some more about the experimental approach in practice, join us for our upcoming on August 19th.

Re-experimenting with my migraines

In reflecting on my blog (below) from 2 years ago,I realised that I had fallen back into the black hole of "business as usual", and my approach to solving the problem was a key part of the problem.

Even though I had recognised previously that my focus on being overtired and stressed was preventing me trying alternatives, I had fallen back into a pattern of just trying to "fix" that probable cause.

Over the last 2 weeks I just happened to avoid my evening sugar hit (I love lollies!), replacing them with fruit and lots of water, and was pleasantly surprised at the result- no migraines!

Now while I'm realistic enough to appreciate that I probably haven't found the magic answer to my migraines, it did serve to remind me that 'just trying stuff' in complex situations is a more appropriate response than staying fixated on our belief in the one answer.

So my experiments continue, to salve my aching head....

I get migraine headaches regularly, and while I take a specific drug to manage them, I'm constantly frustrated by my inability to find a lasting solution.

I had fallen into a pattern of dealing with my migraines as though I knew the problem, that being overtired or stressed were the causes. I would try everything to fix the causes, while using the drugs as necessary.

The problem was that no matter how much I slept more, rested my neck, using relaxation and meditation techniques, it made no difference overall to the frequency of headaches.

My toolkit was exhausted. I didn't know what to do.

So when I recently saw an on-line Migraine Summit advertised, I thought why not see if it can help me with some new ideas.

As I watched a series of webcasts from doctors around the world, something clicked for me. Migraines are really really complex, and my 'cause and effect' thinking, and single solution focus was not helping. I realised that perhaps I needed to let go of my belief that I was in control of what was going on, and that I needed to think and do differently.

So rather than having an answer, I'm taking a different approach. Rather than apply my 'solution' I have set a goal - fewer migraines and fewer drugs - and just try things to see if they get me closer to that goal.

My experiments so far have included tackling mild sleep apnoea, looking at pillow height, diet and hydration, the sequence and type of daily activities, computer usage at night, and sleeping comfort.

And a key in helping me check progress is not a plan forward, but a daily journal of activity, results and learnings from the experiments I am undertaking.

I'm more accepting now that I can't know the answer, and I don't even fully understand the problem, but I'm more confident than before that I'm making real progress towards my goal.

So key realisations for me have been:

- recognising the complexity of my situation

- accepting there is a lot I can't know about this, and I will probably never know the “answer”

- acknowledging that I need to try different things,

- finding ways to keep track of what helps and what doesn’t

- and keep trying….

and I feel a lot better about my slightly less sore head!